|

The use of cosmetics is documented to have begun around 10,000 BC; however, the bulk of our information comes from around 3,000 BC from the written records of the ancient Mesopotamian and Egyptian texts and artifacts. These ancient people were a lot more at ease with their bodies and sexuality compared to the later periods. Both males and females used make-up, had long or short hair as they desired, wore jewelry, coloured their body parts and dressed elaborately and colourfully. Men had no problems wearing skirts and fashion and style was not used to emphasis marked gender differences. However, it did distinguish class and status. Body was used freely and sexuality was often perceived as a gift from gods and goddesses and was celebrated. Judging by the number of nude male and female attendants and personalities depicted, nudity did not seem to be a problem. However, high-ranking females would not expose their bodies as much as the ordinary females did as a sign of their high status.

Scented oils and ointments were used by this time to clean and soften the skin and mask the body odor. Dyes and natural paint was used to colour the face, mainly for ceremonial and religious occasions. Rich people applied minerals to their faces, skin (Iranians use roshoor) and used oiled-based perfumes in their bath. |

Aromatherapy was used extensively by all the major civilizations of the time including the Chinese. An ancient Chinese medical book dated around 2,700 BC contains cures involving over three hundred different aromatic herbs. Traditional Indian medicine, known as Ayurveda, has also used some form of aromatherapy for over 3,000 years. Primitive perfumery probably began with the burning of gums and resins for incense. Eventually, richly scented plants were incorporated into animal and vegetable oils to anoint the body. Even in Neolithic times (7000-4000 BC), the fatty oils of olive and sesame were combined with fragrant plants to create ointments.

Egyptian Papyrus manuscripts as old as 2,700 BC have recorded the use of fragrant herbs, oils, perfumes and temple incense, and mention healing ointments made of fragrant resins. The Epic of Gilgamesh tells of the legendary king of Ur in Mesopotamia (modem Iraq) burning incense made of cedar and myrrh to put the gods and goddesses into a pleasant mood. A tablet from neighboring Babylonia contains an import order for cedar, myrrh and cypress; another gives a recipe for scented ointments; a third suggests medicinal uses for cypress.

Egyptian aromas were potent: pots filled with spices such as frankincense (kondoor) preserved in fat still gave off a faint odor when opened in King Tutankhamen's tomb 3,000 years later. As depicted on wall paintings, solid ointments of spikenard and other aromatics were placed on the heads of dancers and musicians, where they were allowed to gradually—and dramatically—melt down over hair and body while dancing in the temples and for other occasions. People rouged their lips and cheeks, stained their nails with henna, and lined their eyes and eyebrows heavily with kohl (sormeh), a dark-colored powder made of crushed antimony, burnt almonds, lead, oxidized copper, ochre, ash, malachite and chrysocolla—a blue-green copper ore.

Such measures were intended not only to be aesthetically pleasing, but also to protect the individuals from the sun and the dust of the desert. Throughout the African continent, people also coated their skin with fragrant oils for protection. This practice was used extensively in the Mediterranean, where athletes were anointed with scented lotion before competing. Lavender, lily, myrrh, thyme, marjoram, chamomile, peppermint, rosemary, cedar, rose, aloe wood (Ud), olive oil, sesame and almond oil provided the basic ingredients of most perfumes. Many were used in religious rituals and in the process of mummifying and preserving the dead. One of the most common oils was olive oil. The olive is native to Asia Minor and spread from Iran, Syria and Palestine to the rest of the Mediterranean basin 5,000 years ago. It is one of the oldest known cultivated trees. The Phoenicians spread the olive to the Mediterranean shores of Africa and Southern Europe. The olive culture was spread to the early Greeks and eventually to the Romans who spread them all over their territories.

Henna was made from the henna plant and other colours were made from animals, such the blood of black cows. The dyes were sometimes mixed with crushed tadpoles soaked in warm oil for added benefit. Henna was used to colour the hair and to paint body parts such as hands and nails. Thick hair was regarded as the ideal and braided hair extensions were often added to wigs to enhance a woman's appearance. Hairstyles were elaborate and pins were used to hold a wig or extensions in place. Tattooing was also popular and mummies have been discovered with tattoos on their bodies.

Facial masks and frosted make-up was prepared by grinding ant eggs mixed with face paints. In Egypt crocodile excrement was used for mud baths, sheep fat and blood for nail polish, and butter mixed with barley for pimples. All substances were transported and exported all over the area and were commonly used by different nations.

Trade routes to obtain fragrant goods were established throughout the Middle East well before 1,700 BC and were in use for the next 30 centuries, until the Portuguese discovered a way around the Cape of Good Hope in Africa. The Old Testament describes one group of early traders: "a company of Ishmaelites [Arabs] from Gilead, bearing spices, balm and myrrh, going to carry it down to Egypt". As trade routes expanded, Africa, South Arabia and India began to supply spikenard and ginger to Middle Eastern and Mediterranean civilizations. Phoenician merchants traded in Chinese camphor and Indian cinnamon, pepper and sandalwood; Syrians brought fragrant goods to Arabia. Myrrh and frankincense from Yemen reached the Mediterranean by 300 BC, through Persian traders. Traffic on the trade routes boomed as demand increased for roses, sweet flag, narcissus, saffron, mastic, oak moss, cinnamon, cardamom, pepper, nutmeg, ginger, spikenard, aloe, grasses and gum resins. All were used for a number of purposes including making perfumes.

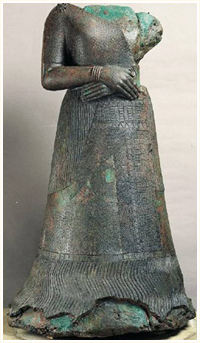

Queen Napir Asu (1400 BC) |

The prosperous ancients were avid consumers of cloths and jewelry. Headgear was popular with both males and females. Kings and queens represented gods and goddesses on earth and both did their best to dress as elegantly, conspicuously and elaborately as gods would. There are magnificent examples of crowns, jewelry and other ornaments at the Mesopotamian sections of all the major museums around the world.

The Elamites in southern Iran formed the earliest city centers in what is now modern Iran. Magnificent artworks and jewelry discovered at Susa and the adjacent city centers show a high level of craftsmanship. The Statue of Queen Napir Asu, currently at the Louvre Museum, shows the fashion styles of the period quite vividly. The Luristan Bronzes from around the first millennium BC also show remarkable craftsmanship and very stylized ornaments, jewelry, pins (dress and hair), etc.

The Iranians arrived relatively late on the scene. By the time the Achaemenid (Hakhamaneshi) were established around 500 BC, there was already 2,500 years of tradition, culture and history in the area. In the beginning, Iranians copied the more established Assyrian, Babylonian and Egyptians, but soon they had their own style and trends. At Persepolis, males from different regions are portrayed wearing their own distinct clothing and headgear. Even Medes (Maad) are distinct from the Persians. On the other hand, Darius (Dariush) while in Egypt is portrayed dressed up as an Egyptian pharaoh (British Museum). The statuettes and other archaeological finds have provided a good picture of the costumes and the jewelry worn at the time. The Oxus treasure at display in the British Museum in London is a good example of jewelry and ornamental styles of the Achaemenid period. |

|